What Is a Distributed System?

A distributed system is a collection of independent computers connected by a communication network that work together to accomplish some goal.

Each computer has its own processor, memory, operating system, and clock. Programs running on different machines cannot directly access each other’s memory or rely on a single shared notion of time. As a result, all coordination must be performed explicitly by sending messages over a network.

A well-designed distributed system often presents itself as a single system image: a collection of independent computers that appears to its users as a single coherent system. The user does not need to know which machine is handling their request, where their data is stored, or how many replicas exist. This abstraction hides the complexity of distribution behind a unified interface.

Failures are expected. In practice, neither the computers nor the communication are assumed to be perfectly reliable. Most of the time, systems behave as expected, but delays, message loss, crashes, and restarts do occur. These failures may affect only part of the system at any given time. Distributed systems are designed with the expectation that such failures will happen occasionally and must be handled explicitly.

Leslie Lamport, one of the pioneers of distributed systems, summarized this reality succinctly:

“You know you have a distributed system when the crash of a computer you’ve never heard of stops you from getting any work done.”

This observation captures the key challenge of distributed systems: components fail independently, and their failures can have system-wide consequences.

Three challenges make distributed systems fundamentally harder than single-machine systems:

-

Partial failure: Components fail independently, leaving the system in an uncertain state between “working” and “broken.”

-

No global knowledge: No shared memory, no shared clock, and no way to observe the complete state of the system at any instant.

-

Unreliable communication: Messages can be delayed, lost, reordered, or duplicated, and network partitions can isolate parts of the system from each other.

These challenges interact in unpleasant ways. Because communication is unreliable, you cannot easily tell whether a remote machine has failed or is merely slow. Because there is no global knowledge, you cannot simply check what another machine is doing. Because failures are partial, you must make decisions and continue operating even when uncertain about the state of other components. We will return to each of these challenges throughout the course.

Distributed Systems Are Older Than You Think

Distributed systems did not emerge with the web or cloud computing. They predate the modern Internet by decades and were driven by many of the same pressures we see today: scale, availability, and coordination across distance.

One of the earliest large-scale distributed systems was the SAGE (Semi-Automatic Ground Environment) air defense system, deployed in 1958 at McGuire Air Force Base in New Jersey. SAGE connected radar stations across North America to a network of 24 large computers, each site built around a pair of IBM AN/FSQ-7 machines. Each site used two interconnected computers so that one could take over if the other failed, an early example of fault tolerance through redundancy.

In 1964, the first online airline reservation system, Sabre, became operational. Sabre ran on two IBM 7090 computers and allowed airlines to manage reservations in real time across geographically distributed terminals. This system introduced many ideas that are still central today: remote access, shared state, concurrency, and the need to maintain consistency despite failures.

What changed dramatically was not the nature of the problems, but the environment in which systems operated. The introduction and widespread adoption of the Internet provided a general-purpose, packet-switched communication infrastructure that made it practical to connect large numbers of machines across organizations and continents. As networking became cheaper and more pervasive, distributed systems moved from specialized, tightly controlled environments into everyday computing.

Modern distributed systems operate at far larger scales and in more hostile environments, but they still struggle with the same fundamental issues of coordination, delay, and partial failure that appeared in these early systems.

Why We Build Distributed Systems

Distributed systems exist because some problems cannot be solved effectively on a single machine.

Scale and the Limits of Vertical Growth

One reason is scale. As demand for computation, storage, and I/O grows, a single machine eventually becomes a bottleneck. Historically, the computing industry relied on faster hardware to address this problem.

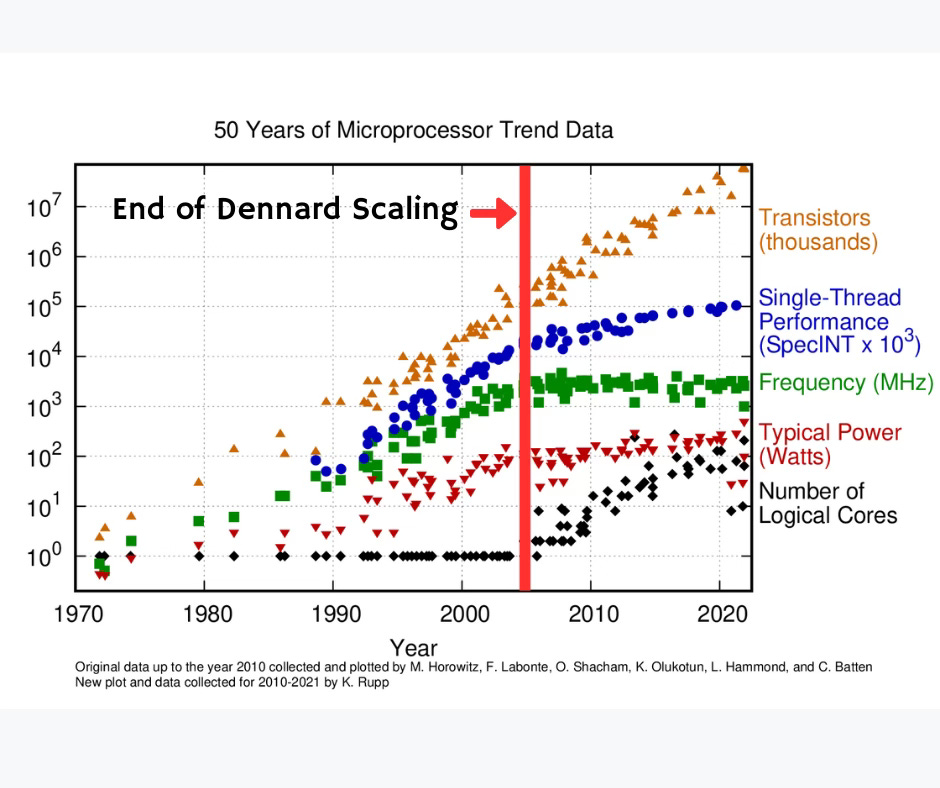

Gordon Moore, a co-founder of Intel, observed in 1965 that the number of transistors on an integrated circuit doubles approximately every 2 years, leading to dramatic performance improvements. This observation, known as Moore’s Law, held for several decades.

Moore’s Law is not a real law, of course. It was just a prediction in the early days of integrated circuits. 1965 was barely five years after the first operational integrated circuit was built and six years before the launch of the first microprocessor, the Intel 4004. However, it’s been used as a guide to drive expectations of processor performance for the past 60+ years.

That trend has been increasingly stressed. Transistors have become smaller, but higher clock speeds lead to excessive power consumption and heat.

A related observation, Dennard scaling, predicted that as transistors shrank, their power consumption would decrease proportionally, allowing clock speeds to increase without increasing overall power. Dennard scaling broke down in the early 2000s. Smaller transistors no longer meant proportionally lower power, which meant that increasing clock speeds led to chips that ran too hot to cool effectively. This is why processor clock speeds largely plateaued around 3 to 4 GHz.

In the early 2000s, performance gains shifted from faster single cores to multiple cores per chip, which in turn requires parallel programming.

Beyond that, systems increasingly rely on heterogeneous computing, which places a variety of computing elements, such as GPUs, neural processing units, and other specialized accelerators, on a single chip.

Even more recently, System Technology Co-Optimization (STCO) focuses on using the principles of heterogeneous computing but optimizing entire systems rather than individual transistors.

Our observations only focused on increasing the performance of processors. Memory bottlenecks become a real issue, especially as CPUs get more cores. More broadly, the bandwidth to storage and the network also become limiting factors.

The key point is that we can no longer expect single machines to get “fast enough” to solve our problems. Performance gains from hardware alone are no longer sufficient, which pushes us toward distributed solutions.

Vertical vs. Horizontal Scaling

Vertical scaling (scaling up) increases the capacity of a single machine by adding faster CPUs, more cores, more memory, or larger disks. This approach is limited by hardware constraints, power, cost, and diminishing returns.

Horizontal scaling (scaling out) increases capacity by adding more machines and distributing computation or data across them. Distributed systems are fundamentally about enabling horizontal scaling.

Closely related is Amdahl’s Law, which predicts the theoretical speedup of a process when only parts of it can be parallelized, but also points out that parallel speedup is limited by the portion of a task that cannot be parallelized. Even with many cores or machines, sequential components quickly become bottlenecks.

Collaboration and Network Effects

Distributed systems enable collaboration. Many modern applications derive their value from connecting users and services rather than from raw computation alone. Social networks, collaborative editing, online gaming, and marketplaces all depend on interactions among many participants.

This is often described by Metcalfe’s Law, which states that the value of a network grows roughly with the square of the number of connected users. While not a precise law (neither are Moore’s Law nor Amdahl’s Law), it captures an important intuition: connectivity itself creates value, and that value depends on distributed infrastructure.

Reduced Latency

Geographic distribution allows systems to reduce latency by placing data and computation closer to users. Content delivery networks, regional data centers, and edge computing all exploit this idea. Rather than serving every request from a single location, systems distribute replicas or cached data across the network to improve responsiveness.

Mobility and Ubiquitous Computing

Mobility is another major driver. Distributed systems are no longer just about desktops and servers. Phones, tablets, cars, sensors, cameras, and other embedded devices all participate in distributed systems. There are now more deployed IoT (Internet-of-Things) devices than traditional computers.

These devices move, disconnect, reconnect, and operate under varying network conditions. Distributed systems provide the infrastructure that allows them to function coherently despite these constraints.

Incremental Growth and Cost

Distributed systems also support incremental growth. A service does not need to be built at full scale from the beginning. It can start on a small number of machines and grow over time as demand increases.

Google is a good example of this model. The earliest versions of Google ran on a small number of commodity machines in a single location at Stanford. As usage grew, the system scaled by adding more machines, then more racks, and eventually multiple data centers around the world. The basic approach did not change: distribute data and computation across machines. The core frameworks that enabled Google search, like the Google File System and map-reduce computation, were designed to scale to an arbitrary number of servers.

Delegated Infrastructure and Operations

Distributed systems allow organizations to offload infrastructure responsibilities. Rather than purchasing, configuring, and maintaining physical servers, an organization can use third-party services for storage, computing, databases, and other functions.

This delegation offers several advantages:

-

Deployment is faster because there is no need to provision hardware.

-

The operational burden shifts to the service provider, which handles backups, security patches, and capacity planning.

-

Services can be modular and handled by different providers: one provider handles email, another handles file storage, another handles authentication.

Cloud computing is the most prominent example of this pattern:

-

Infrastructure-as-a-Service (IaaS) providers offer virtual machines, storage, and networking on demand.

-

Platform-as-a-Service (PaaS) providers offer higher-level abstractions, such as managed databases and application runtimes.

-

Software-as-a-Service (SaaS) providers offer complete applications accessible over the network.

The tradeoff is dependency. When infrastructure is delegated, the organization depends on the provider’s availability, performance, and security practices. This is another form of distributed system design: the system’s boundaries extend beyond the organization’s own machines.

Transparency as a Design Goal

A goal in the design of many distributed systems is transparency: hiding the fact that resources are distributed across multiple computers. When transparency is achieved, users and applications interact with the system as if it were a single machine.

There are several forms of transparency:

Location transparency means that users and programs do not need to know where resources are physically located. A file, service, or data item can be accessed by name without knowing which machine hosts it.

Migration transparency means that resources can move from one machine to another without affecting how they are accessed. A service can be relocated for load balancing or maintenance without breaking clients.

Replication transparency means that users cannot tell whether they are accessing one copy of a resource or one of many replicas. The system handles replica selection and consistency internally.

Concurrency transparency means that multiple users can access shared resources simultaneously without interfering with each other. The system manages coordination and synchronization behind the scenes.

Failure transparency means that the system masks failures from users. If a component fails, the system recovers or routes around the failure without exposing the problem to the application.

Parallelism transparency means that operations may be executed in parallel across multiple machines without the user’s knowledge. A query might span dozens of servers, but the user sees only a single result.

Full transparency is rarely achievable in practice. Network delays, partial failures, and consistency constraints often leak through the abstraction. But transparency remains a useful design goal because it simplifies the mental model for users and application developers.

All-or-Nothing Failure vs. Partial Failure

In a centralized system, failures are typically all-or-nothing. If the system crashes, everything stops. If it is running, everything works.

Distributed systems behave differently. Components can fail independently. One server may crash while others continue to operate. A network link may fail while the machines on either side remain functional. A slow response may be indistinguishable from a failed component.

This phenomenon is called partial failure, and it is one of the defining challenges of distributed systems. The system must continue operating despite incomplete, delayed, or incorrect information about which components are functioning.

Fault Tolerance and Redundancy

Because failures are expected, distributed systems are designed to tolerate them rather than avoid them entirely.

Fault tolerance involves detecting failures, recovering from them, and continuing to provide service. A central goal is to avoid single points of failure, where the failure of one component brings down the entire system.

Redundancy is the primary tool for achieving this. By replicating components, a system can continue operating even if some replicas fail.

Availability vs. Reliability

Reliability concerns correctness and time-to-failure: whether a system produces correct results and how long it operates before something breaks.

Availability measures the fraction of time a system is usable from a client’s perspective.

A system can be highly available but not reliable, occasionally returning stale or inconsistent results. For example, a server may not get the latest updates to date because a network link was down, but return its older versions.

Conversely, a system can be reliable, but not highly available. In the same example scenario, a system may choose to not respond to a client’s request until it is certain that its version of data is consistent.

Distributed systems often prioritize availability using redundancy, which introduces consistency challenges.

Measuring Availability in Nines

Availability is often expressed as a count of nines. “Five nines” means 99.999% availability, or roughly 5 minutes of downtime per year. Each additional nine represents a tenfold improvement.

| Nines | Availability | Downtime per year |

|---|---|---|

| Two nines | 99% | 3.65 days |

| Three nines | 99.9% | 8.76 hours |

| Four nines | 99.99% | 52.6 minutes |

| Five nines | 99.999% | 5.26 minutes |

Note that downtime must factor in planned outages, like software updates and hardware upgrades. Cloud providers typically offer three to four nines in their SLAs (service level agreements). Achieving five nines requires careful redundancy and is expensive to maintain.

Series and Parallel Systems

The way components are combined has a dramatic effect on system reliability and availability. Two simple models capture this difference: series systems and parallel systems.

Series systems (all-or-nothing)

In a series system, every component must be functioning correctly for the system to work. If any component fails, the entire system fails.

This is the default behavior of many naïve designs. For example, if a service requires a database server, an authentication server, a logging service, and a configuration service to all be reachable before it can process requests, then the failure of any one of these components makes the service unavailable.

If a system consists of n independent components, each with failure probability Pi, then the probability that the system is operational is:

\[P(\text{system works}) = \prod_{i=1}^{n} (1 - P_i)\]

The probability that the system fails is therefore:

\[P(\text{system fails}) = 1 - \prod_{i=1}^{n} (1 - P_i)\]

As n grows, the probability that something is broken approaches 1, even if individual components are quite reliable. This is why large systems built as series dependencies tend to be unavailable much of the time. With enough components, something is always failing.

This is the essence of all-or-nothing failure.

Example: A Chain of Microservices

Consider a mobile app that displays a user’s profile. To render the page, the app must contact four services in sequence: an API gateway, an authentication service, a user profile service, and a database.

Suppose each service is available 99% of the time. Because these are arranged in series, the overall availability is:

0.99 × 0.99 × 0.99 × 0.99 = 0.96 = 96%

The system is down over 4% of the time, even though each individual component is highly reliable. Adding a fifth 99%-available service drops availability to about 95%. This is why microservice architectures must be designed carefully to avoid long chains of hard dependencies.

Parallel systems (fault-tolerant)

In a parallel system, components provide redundancy. The system continues to operate as long as at least one component is functioning.

A common example is a replicated service behind a load balancer. If one replica crashes, requests can be routed to another. From the client’s perspective, the service remains available.

If two independent components each fail with probability P, then the system fails only if both fail:

\[P(\text{system fails}) = P^2\]

More generally, for n replicated components:

\[P(\text{system fails}) = \prod_{i=1}^{n} P_i\]

Even modest replication can dramatically improve availability. For example, two components that are each available 95% of the time yield a system availability of 99.75% when used in parallel.

Example: Replicated Web Servers

A website runs on three identical servers behind a load balancer. Each server has an availability of 95% (meaning it is down 5% of the time, on average).

With parallel redundancy, the site fails only if all three servers are down simultaneously. The probability of total failure is:

0.05 × 0.05 × 0.05 = 0.000125

This means the system is available 99.9875% of the time. By adding just two extra servers, availability improved from 95% to nearly 99.99%. This dramatic improvement explains why replication is the foundation of fault-tolerant design.

These simple models explain several core design principles in distributed systems:

-

Requiring all components to be operational is a losing proposition at scale.

-

High availability comes from structuring systems so that components fail independently and redundantly.

-

Adding features or services as hard dependencies reduces availability unless those services are themselves replicated.

Fault tolerance is as much about system structure as it is about component reliability.

This is why distributed systems are designed to avoid single points of failure and minimize long dependency chains. The goal is not to prevent failures, but to ensure that failures do not propagate into system-wide outages.

An important caveat

These probability calculations are basic examples to illustrate the models. They assume independent failures. In real systems, failures are often correlated. Power outages, network partitions, software bugs, and misconfigurations can take down multiple replicas at once.

This is why simply adding replicas is not enough. Where replicas are placed, how they are managed, and how they fail all matter. We will return to this issue when we discuss replication strategies, failure domains, and consensus.

Failure Models

Different types of failures lead to different design assumptions.

In a fail-silent failure (also called a crash failure), a component halts execution and produces no further output. It does not send erroneous messages; it simply stops responding. This model captures crashes and power failures and is a useful starting point for reasoning about distributed systems.

However, in a distributed system, a component that has failed silently is often indistinguishable from one that is slow or temporarily unreachable due to network delays or partitions. This creates a challenge: how do you know if a remote process has crashed or is just taking a long time to respond?

A fail-stop failure is an idealized model that makes a stronger assumption: when a component fails, other components can eventually detect the failure. This might happen via a reliable failure detector, a heartbeat mechanism, or some other notification system. While fail-stop simplifies reasoning about fault tolerance, the assumption of reliable failure detection is often optimistic in real life.

In a fail-restart failure, a component crashes and later restarts. Restarted components may have stale state, which introduces additional complexity. The component must recognize that it has restarted and may have obsolete information.

Network failures include message omission (where messages get lost), excessive delays, and partitions, where the network splits into disconnected sub-networks.

In Byzantine failures, a component continues to run but does not behave according to the system’s specification. It may send incorrect, inconsistent, or misleading messages, either due to software bugs, hardware faults, or malicious behavior.

Most systems choose a failure model that matches their expected environment rather than attempting to handle all possible failures.

Network Timing Models

The behavior of a distributed system depends heavily on assumptions about message delivery times. Different timing models lead to different design possibilities.

In a synchronous network model, there is a known upper bound on message delivery time. If a message is sent, it will arrive within some time T. This assumption makes failure detection straightforward: if a node does not respond within T, it can be assumed to have failed. Synchronous models are useful for analysis but rarely match real networks.

In a partially synchronous network model, an upper bound on message delivery exists, but the system does not know what it is in advance. The bound may need to be discovered through observation, or the system may only behave correctly when messages happen to arrive within some (unknown) time limit. Many practical systems operate under partial synchrony assumptions.

In an asynchronous network model, messages can take arbitrarily long to arrive. There is no upper bound on delivery time. This is the model that best describes message delivery on the Internet: packets can be delayed indefinitely by congestion, routing changes, or transient failures.

Asynchronous networks create significant challenges. A slow response is indistinguishable from a failed node. A message that appears lost may simply be delayed. Retransmissions can create duplicates. Messages sent in one order may arrive in a different order. Protocols designed for asynchronous networks must handle all of these possibilities without relying on timing assumptions.

The choice of timing model affects what guarantees a system can provide. Some problems, such as consensus, are provably impossible to solve in purely asynchronous networks with even a single faulty node. Practical systems work around this by making partial synchrony assumptions or by accepting weaker guarantees.

Caching vs. Replication

Caching and replication are often confused, but they serve different purposes.

Replication creates multiple authoritative copies of data or services. The goal is availability and fault tolerance. If one replica fails, another can take over. All replicas are part of the system’s source of truth and must be kept consistent with each other, which requires coordination.

Caching stores temporary copies of data closer to where it is needed. The goal is performance. A cache reduces latency by avoiding repeated trips to the authoritative source. Cached data may become stale, and this is generally acceptable. If a cache fails or is cleared, the data can always be retrieved again from the source.

The critical difference between the two is the nature of the copy. A cache is derived from an authoritative source and is expendable by design: it’s ok if the data disappears. A replica is an authoritative source. Even when you have multiple replicas, each one holds data that must be preserved and kept consistent with the others.

This difference shows up in how you treat failures. A cache miss is routine: the system simply fetches the data from the origin, and the only cost is latency. A replica failure triggers recovery: the system must restore the replica, resynchronize its state, and ensure it is consistent with the other replicas before it can serve requests again.

Let’s consider a couple of examples.

- Caching:

- A CDN (content delivery network) edge server holding a copy of a product image is a cache. If that edge server crashes, the image is still safe at the origin server. The next user request takes longer because it must be served from the origin, but the failure requires no special recovery.

- Replication:

- A database storing customer orders might be replicated across three servers for fault tolerance. If one replica fails, the data is safe on the other two, but the failed replica must be rebuilt and synchronized before it rejoins the cluster. The system treats replica loss as an event that requires corrective action, not just a performance hit.

Both caching and replication introduce consistency challenges, but the tradeoffs differ. With caching, the question is how stale you can tolerate the data being. With replication, the question is how to keep multiple authoritative copies synchronized, especially when failures occur. We will explore replication strategies and consistency models in detail later in the course.

No Global Knowledge

There is no global view of a distributed system.

Each component knows only its own state and whatever information it has received from others, which may be delayed or outdated. There is no single place where the “true” system state can be observed.

As a result, failure detection is inherently imperfect. A component that appears to be down may simply be slow or unreachable. Distributed systems must operate despite this uncertainty.

Security

Security in distributed systems is fundamentally different from security in traditional single-machine systems.

In a centralized system, the operating system manages security. Users authenticate to the system, receive a user ID, and access control decisions are made based on that identity. The trusted computing base is confined to a single machine.

In a distributed system, this model breaks down. Services run on remote machines that may be operated by different organizations. Communication travels over public networks. Users may authenticate to one service and expect that identity to be recognized by others. Services make access control decisions rather than the operating system. The boundaries of trust are no longer clear.

Distributed systems must address several security concerns. Authentication establishes who is making a request. Authorization determines what the requester is allowed to do. Encryption protects data in transit from eavesdropping. Integrity checking detects tampering with messages. Audit logging records actions for later review.

Cryptography is the foundation for most of these mechanisms. Hashes verify integrity. Digital signatures provide authentication and non-repudiation. Encryption protects confidentiality. Key management determines who can access what. We will cover these later in the course (at a high level; take 419 for more details).

Users also expect convenience. Single sign-on allows a user to authenticate once and access multiple services. Delegated authorization allows a user to grant limited access to a third-party service without sharing credentials. These conveniences introduce their own complexity and attack surface.

Service Architectures

Distributed systems can be organized in many ways. The choice of architecture affects scalability, fault tolerance, and complexity.

Client-Server

The client-server model is the simplest distributed architecture. Clients send requests to servers, which process them and return responses. A server is a machine (or process) that provides a service. Clients do not communicate directly with each other.

This model is easy to understand and manage. The server is the single source of truth for its service. However, the server can become a bottleneck or a single point of failure. Scaling requires either upgrading the server (vertical scaling) or distributing requests across multiple servers (horizontal scaling with load balancing).

Multi-Tier Architectures

A multi-tier architecture (also called n-tier) extends the client-server model by introducing intermediate layers. Each tier handles a specific concern and communicates only with adjacent tiers.

A classic three-tier architecture separates presentation (the user interface), application logic (business rules and processing), and data storage (databases). The client handles the presentation. A middle tier handles application logic, connection management, and coordination. A back-end tier handles persistent storage.

Multi-tier architectures allow each tier to be scaled and managed independently. The middle tier can handle tasks such as load balancing, caching, request queuing, and transaction coordination. Additional tiers can be inserted transparently, such as firewalls, caches, or API gateways.

Microservices

A microservices architecture decomposes an application into a collection of small, autonomous services. Each service runs independently, has a well-defined interface, and can be developed, deployed, and scaled separately.

Unlike multi-tier architectures, microservices do not enforce a strict layering. Services communicate with each other as needed, often forming a complex graph of dependencies. A client request might touch a dozen services before producing a response.

Microservices offer flexibility. Teams can develop and deploy services independently using different languages or frameworks. Services can be scaled individually based on demand. Failures can be isolated to individual services rather than bringing down the entire application.

The tradeoff is complexity. Coordinating many services requires careful attention to interfaces, versioning, and failure handling. Debugging becomes harder when a request flows through many services. The system must handle partial failures gracefully. As discussed earlier, long chains of service dependencies can dramatically reduce overall availability.

Peer-to-Peer

In a peer-to-peer (P2P) model, there is no central server. All participants (peers) are equal and communicate directly with each other. Each peer can act as both client and server.

Peer-to-peer systems aim for robustness and self-scalability. There is no single point of failure. As more peers join, the system’s capacity increases. BitTorrent is a classic example: peers share pieces of files with each other, distributing both the storage and the bandwidth load. We will cover this and other models later in the course.

Pure peer-to-peer systems are rare in practice. Most P2P systems use a hybrid P2P model, where a central server handles coordination tasks such as user lookup, content indexing, or session initiation, while peers handle the traffic-intensive work of data transfer.

Worker Pools and Compute Clusters

A worker pool (sometimes called a processor pool or compute cluster) maintains a collection of computing resources that can be assigned to tasks on demand. A coordinator receives work requests and dispatches them to available workers. Render farms for movie production, batch processing systems, and machine learning training clusters often follow this pattern.

This model separates the submission of work from its execution. Jobs can be queued, prioritized, and distributed across available resources. The pool can grow or shrink based on demand.

Cloud Computing

Cloud computing provides computing resources as a network service. Rather than owning and operating physical infrastructure, organizations rent capacity from providers who manage the underlying hardware.

Major Cloud Providers

The cloud computing market is dominated by a few major providers. Amazon Web Services (AWS) is the largest, followed by Microsoft Azure and Google Cloud Platform (GCP).

Other large providers include IBM Cloud, Oracle Cloud, and Alibaba Cloud. Each provider offers comparable services under different names: for example, virtual machine services are called EC2 on AWS, Virtual Machines on Azure, and Compute Engine on Google Cloud. When reading documentation or job postings, you will encounter these provider-specific names frequently.

Cloud services are typically categorized by the level of abstraction they provide:

Software as a Service (SaaS) delivers complete applications over the network. The customer uses the application but does not manage any infrastructure. Examples include Google Workspace, Microsoft 365, Slack, Zoom, and Salesforce.

Platform as a Service (PaaS) provides a higher-level environment for running applications. The provider manages the operating system, runtime, and middleware. The customer deploys application code. Examples include Google App Engine, AWS Elastic Beanstalk, Azure App Service, and Heroku.

Infrastructure as a Service (IaaS) provides virtual machines, storage, and networking. The customer controls the operating system and everything above it. Examples include Amazon EC2, Google Compute Engine, and Microsoft Azure Virtual Machines.

Cloud computing enables rapid deployment, elastic scaling, and reduced operational burden. It also introduces dependency on the provider’s availability, performance, and pricing decisions.

Beyond the core three categories, several specialized service models have emerged:

Function as a Service (FaaS) provides event-driven compute where users deploy individual functions rather than applications. The provider handles all scaling automatically, and users pay only for execution time. This model is often called serverless computing. Examples include AWS Lambda, Google Cloud Functions, Azure Functions, and Cloudflare Workers.

Container as a Service (CaaS) offers managed container orchestration where users deploy containerized applications without managing the underlying cluster infrastructure. It sits between IaaS and PaaS in abstraction level. Examples include AWS ECS, Google Kubernetes Engine, Azure Kubernetes Service, and AWS Fargate.

Database as a Service (DBaaS) delivers managed database systems where the provider handles provisioning, patching, backups, and scaling. Users interact with the database through standard interfaces without managing the underlying servers. Examples include AWS RDS, Google Cloud SQL, MongoDB Atlas, and Azure Cosmos DB.

Storage as a Service (STaaS) provides object, block, or file storage delivered over the network. While often bundled under IaaS, storage services are distinct enough that providers offer them as standalone products with their own pricing and APIs. Examples include AWS S3, Google Cloud Storage, Azure Blob Storage, and Backblaze B2.

Summary

Distributed systems exist because single machines are no longer sufficient to meet demands for scale, availability, latency, collaboration, mobility, and delegated operations.

They are difficult because components operate independently, communicate over unreliable networks, and fail independently. There is no shared memory, no shared clock, and no global view of system state. Failures are partial rather than all-or-nothing, and slow responses are often indistinguishable from failures.

Designing distributed systems requires choosing appropriate failure models, timing assumptions, and architectural patterns. Transparency hides the complexity of distribution from users, but that abstraction is inherently leaky. Security must be built in from the start, not bolted on afterward.

These constraints shape every design decision that follows in this course.

Further Reading

- Lampson, B.W. Hints for Computer System Design. ACM SIGOPS Operating Systems Review, Vol. 17, No. 5, October 1983, pp. 33-48. (A somewhat old but classic paper that will give you a deeper understanding of the challenges of building reliable systems from unreliable components)